The Go Blog

Profiling Go Programs

At Scala Days 2011, Robert Hundt presented a paper titled Loop Recognition in C++/Java/Go/Scala. The paper implemented a specific loop finding algorithm, such as you might use in a flow analysis pass of a compiler, in C++, Go, Java, Scala, and then used those programs to draw conclusions about typical performance concerns in these languages. The Go program presented in that paper runs quite slowly, making it an excellent opportunity to demonstrate how to use Go’s profiling tools to take a slow program and make it faster.

By using Go’s profiling tools to identify and correct specific bottlenecks, we can make the Go loop finding program run an order of magnitude faster and use 6x less memory.

(Update: Due to recent optimizations of libstdc++ in gcc, the memory reduction is now 3.7x.)

Hundt’s paper does not specify which versions of the C++, Go, Java, and Scala

tools he used.

In this blog post, we will be using the most recent weekly snapshot of the 6g

Go compiler and the version of g++ that ships with the Ubuntu Natty

distribution.

(We will not be using Java or Scala, because we are not skilled at writing efficient

programs in either of those languages, so the comparison would be unfair.

Since C++ was the fastest language in the paper, the comparisons here with C++ should

suffice.)

(Update: In this updated post, we will be using the most recent development snapshot

of the Go compiler on amd64 and the most recent version of g++ – 4.8.0, which was

released in March 2013.)

$ go version

go version devel +08d20469cc20 Tue Mar 26 08:27:18 2013 +0100 linux/amd64

$ g++ --version

g++ (GCC) 4.8.0

Copyright (C) 2013 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

...

$

The programs are run on a computer with a 3.4GHz Core i7-2600 CPU and 16 GB of RAM running Gentoo Linux’s 3.8.4-gentoo kernel. The machine is running with CPU frequency scaling disabled via

$ sudo bash

# for i in /sys/devices/system/cpu/cpu[0-7]

do

echo performance > $i/cpufreq/scaling_governor

done

#

We’ve taken Hundt’s benchmark programs

in C++ and Go, combined each into a single source file, and removed all but one

line of output.

We’ll time the program using Linux’s time utility with a format that shows user time,

system time, real time, and maximum memory usage:

$ cat xtime

#!/bin/sh

/usr/bin/time -f '%Uu %Ss %er %MkB %C' "$@"

$

$ make havlak1cc

g++ -O3 -o havlak1cc havlak1.cc

$ ./xtime ./havlak1cc

# of loops: 76002 (total 3800100)

loop-0, nest: 0, depth: 0

17.70u 0.05s 17.80r 715472kB ./havlak1cc

$

$ make havlak1

go build havlak1.go

$ ./xtime ./havlak1

# of loops: 76000 (including 1 artificial root node)

25.05u 0.11s 25.20r 1334032kB ./havlak1

$

The C++ program runs in 17.80 seconds and uses 700 MB of memory.

The Go program runs in 25.20 seconds and uses 1302 MB of memory.

(These measurements are difficult to reconcile with the ones in the paper, but the

point of this post is to explore how to use go tool pprof, not to reproduce the

results from the paper.)

To start tuning the Go program, we have to enable profiling.

If the code used the Go testing package’s

benchmarking support, we could use gotest’s standard -cpuprofile and -memprofile

flags.

In a standalone program like this one, we have to import runtime/pprof and add a few

lines of code:

var cpuprofile = flag.String("cpuprofile", "", "write cpu profile to file")

func main() {

flag.Parse()

if *cpuprofile != "" {

f, err := os.Create(*cpuprofile)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

pprof.StartCPUProfile(f)

defer pprof.StopCPUProfile()

}

...

The new code defines a flag named cpuprofile, calls the

Go flag library to parse the command line flags,

and then, if the cpuprofile flag has been set on the command line,

starts CPU profiling

redirected to that file.

The profiler requires a final call to

StopCPUProfile to

flush any pending writes to the file before the program exits; we use defer

to make sure this happens as main returns.

After adding that code, we can run the program with the new -cpuprofile flag

and then run go tool pprof to interpret the profile.

$ make havlak1.prof

./havlak1 -cpuprofile=havlak1.prof

# of loops: 76000 (including 1 artificial root node)

$ go tool pprof havlak1 havlak1.prof

Welcome to pprof! For help, type 'help'.

(pprof)

The go tool pprof program is a slight variant of

Google’s pprof C++ profiler.

The most important command is topN, which shows the top N samples in the profile:

(pprof) top10

Total: 2525 samples

298 11.8% 11.8% 345 13.7% runtime.mapaccess1_fast64

268 10.6% 22.4% 2124 84.1% main.FindLoops

251 9.9% 32.4% 451 17.9% scanblock

178 7.0% 39.4% 351 13.9% hash_insert

131 5.2% 44.6% 158 6.3% sweepspan

119 4.7% 49.3% 350 13.9% main.DFS

96 3.8% 53.1% 98 3.9% flushptrbuf

95 3.8% 56.9% 95 3.8% runtime.aeshash64

95 3.8% 60.6% 101 4.0% runtime.settype_flush

88 3.5% 64.1% 988 39.1% runtime.mallocgc

When CPU profiling is enabled, the Go program stops about 100 times per second

and records a sample consisting of the program counters on the currently executing

goroutine’s stack.

The profile has 2525 samples, so it was running for a bit over 25 seconds.

In the go tool pprof output, there is a row for each function that appeared in

a sample.

The first two columns show the number of samples in which the function was running

(as opposed to waiting for a called function to return), as a raw count and as a

percentage of total samples.

The runtime.mapaccess1_fast64 function was running during 298 samples, or 11.8%.

The top10 output is sorted by this sample count.

The third column shows the running total during the listing:

the first three rows account for 32.4% of the samples.

The fourth and fifth columns show the number of samples in which the function appeared

(either running or waiting for a called function to return).

The main.FindLoops function was running in 10.6% of the samples, but it was on the

call stack (it or functions it called were running) in 84.1% of the samples.

To sort by the fourth and fifth columns, use the -cum (for cumulative) flag:

(pprof) top5 -cum

Total: 2525 samples

0 0.0% 0.0% 2144 84.9% gosched0

0 0.0% 0.0% 2144 84.9% main.main

0 0.0% 0.0% 2144 84.9% runtime.main

0 0.0% 0.0% 2124 84.1% main.FindHavlakLoops

268 10.6% 10.6% 2124 84.1% main.FindLoops

(pprof) top5 -cum

In fact the total for main.FindLoops and main.main should have been 100%, but

each stack sample only includes the bottom 100 stack frames; during about a quarter

of the samples, the recursive main.DFS function was more than 100 frames deeper

than main.main so the complete trace was truncated.

The stack trace samples contain more interesting data about function call relationships

than the text listings can show.

The web command writes a graph of the profile data in SVG format and opens it in a web

browser.

(There is also a gv command that writes PostScript and opens it in Ghostview.

For either command, you need graphviz installed.)

(pprof) web

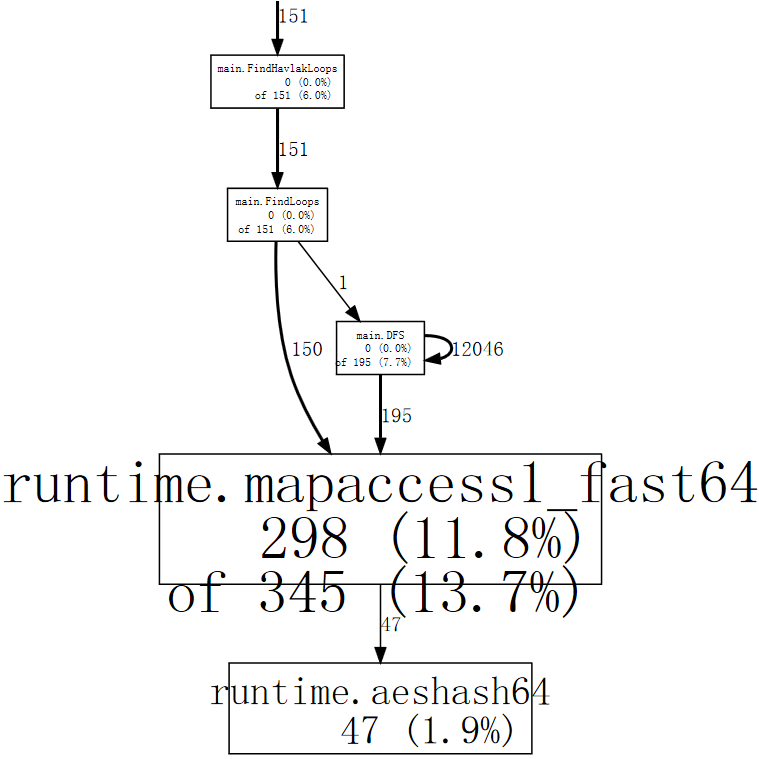

A small fragment of the full graph looks like:

Each box in the graph corresponds to a single function, and the boxes are sized

according to the number of samples in which the function was running.

An edge from box X to box Y indicates that X calls Y; the number along the edge is

the number of times that call appears in a sample.

If a call appears multiple times in a single sample, such as during recursive function

calls, each appearance counts toward the edge weight.

That explains the 21342 on the self-edge from main.DFS to itself.

Just at a glance, we can see that the program spends much of its time in hash

operations, which correspond to use of Go’s map values.

We can tell web to use only samples that include a specific function, such as

runtime.mapaccess1_fast64, which clears some of the noise from the graph:

(pprof) web mapaccess1

If we squint, we can see that the calls to runtime.mapaccess1_fast64 are being

made by main.FindLoops and main.DFS.

Now that we have a rough idea of the big picture, it’s time to zoom in on a particular

function.

Let’s look at main.DFS first, just because it is a shorter function:

(pprof) list DFS

Total: 2525 samples

ROUTINE ====================== main.DFS in /home/rsc/g/benchgraffiti/havlak/havlak1.go

119 697 Total samples (flat / cumulative)

3 3 240: func DFS(currentNode *BasicBlock, nodes []*UnionFindNode, number map[*BasicBlock]int, last []int, current int) int {

1 1 241: nodes[current].Init(currentNode, current)

1 37 242: number[currentNode] = current

. . 243:

1 1 244: lastid := current

89 89 245: for _, target := range currentNode.OutEdges {

9 152 246: if number[target] == unvisited {

7 354 247: lastid = DFS(target, nodes, number, last, lastid+1)

. . 248: }

. . 249: }

7 59 250: last[number[currentNode]] = lastid

1 1 251: return lastid

(pprof)

The listing shows the source code for the DFS function (really, for every function

matching the regular expression DFS).

The first three columns are the number of samples taken while running that line, the

number of samples taken while running that line or in code called from that line, and

the line number in the file.

The related command disasm shows a disassembly of the function instead of a source

listing; when there are enough samples this can help you see which instructions are

expensive.

The weblist command mixes the two modes: it shows

a source listing in which clicking a line shows the disassembly.

Since we already know that the time is going into map lookups implemented by the

hash runtime functions, we care most about the second column.

A large fraction of time is spent in recursive calls to DFS (line 247), as would be

expected from a recursive traversal.

Excluding the recursion, it looks like the time is going into the accesses to the

number map on lines 242, 246, and 250.

For that particular lookup, a map is not the most efficient choice.

Just as they would be in a compiler, the basic block structures have unique sequence

numbers assigned to them.

Instead of using a map[*BasicBlock]int we can use a []int, a slice indexed by the

block number.

There’s no reason to use a map when an array or slice will do.

Changing number from a map to a slice requires editing seven lines in the program

and cut its run time by nearly a factor of two:

$ make havlak2

go build havlak2.go

$ ./xtime ./havlak2

# of loops: 76000 (including 1 artificial root node)

16.55u 0.11s 16.69r 1321008kB ./havlak2

$

(See the diff between havlak1 and havlak2)

We can run the profiler again to confirm that main.DFS is no longer a significant

part of the run time:

$ make havlak2.prof

./havlak2 -cpuprofile=havlak2.prof

# of loops: 76000 (including 1 artificial root node)

$ go tool pprof havlak2 havlak2.prof

Welcome to pprof! For help, type 'help'.

(pprof)

(pprof) top5

Total: 1652 samples

197 11.9% 11.9% 382 23.1% scanblock

189 11.4% 23.4% 1549 93.8% main.FindLoops

130 7.9% 31.2% 152 9.2% sweepspan

104 6.3% 37.5% 896 54.2% runtime.mallocgc

98 5.9% 43.5% 100 6.1% flushptrbuf

(pprof)

The entry main.DFS no longer appears in the profile, and the rest of the program

runtime has dropped too.

Now the program is spending most of its time allocating memory and garbage collecting

(runtime.mallocgc, which both allocates and runs periodic garbage collections,

accounts for 54.2% of the time).

To find out why the garbage collector is running so much, we have to find out what is

allocating memory.

One way is to add memory profiling to the program.

We’ll arrange that if the -memprofile flag is supplied, the program stops after one

iteration of the loop finding, writes a memory profile, and exits:

var memprofile = flag.String("memprofile", "", "write memory profile to this file")

...

FindHavlakLoops(cfgraph, lsgraph)

if *memprofile != "" {

f, err := os.Create(*memprofile)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

pprof.WriteHeapProfile(f)

f.Close()

return

}

We invoke the program with -memprofile flag to write a profile:

$ make havlak3.mprof

go build havlak3.go

./havlak3 -memprofile=havlak3.mprof

$

(See the diff from havlak2)

We use go tool pprof exactly the same way. Now the samples we are examining are

memory allocations, not clock ticks.

$ go tool pprof havlak3 havlak3.mprof

Adjusting heap profiles for 1-in-524288 sampling rate

Welcome to pprof! For help, type 'help'.

(pprof) top5

Total: 82.4 MB

56.3 68.4% 68.4% 56.3 68.4% main.FindLoops

17.6 21.3% 89.7% 17.6 21.3% main.(*CFG).CreateNode

8.0 9.7% 99.4% 25.6 31.0% main.NewBasicBlockEdge

0.5 0.6% 100.0% 0.5 0.6% itab

0.0 0.0% 100.0% 0.5 0.6% fmt.init

(pprof)

The command go tool pprof reports that FindLoops has allocated approximately

56.3 of the 82.4 MB in use; CreateNode accounts for another 17.6 MB.

To reduce overhead, the memory profiler only records information for approximately

one block per half megabyte allocated (the “1-in-524288 sampling rate”), so these

are approximations to the actual counts.

To find the memory allocations, we can list those functions.

(pprof) list FindLoops

Total: 82.4 MB

ROUTINE ====================== main.FindLoops in /home/rsc/g/benchgraffiti/havlak/havlak3.go

56.3 56.3 Total MB (flat / cumulative)

...

1.9 1.9 268: nonBackPreds := make([]map[int]bool, size)

5.8 5.8 269: backPreds := make([][]int, size)

. . 270:

1.9 1.9 271: number := make([]int, size)

1.9 1.9 272: header := make([]int, size, size)

1.9 1.9 273: types := make([]int, size, size)

1.9 1.9 274: last := make([]int, size, size)

1.9 1.9 275: nodes := make([]*UnionFindNode, size, size)

. . 276:

. . 277: for i := 0; i < size; i++ {

9.5 9.5 278: nodes[i] = new(UnionFindNode)

. . 279: }

...

. . 286: for i, bb := range cfgraph.Blocks {

. . 287: number[bb.Name] = unvisited

29.5 29.5 288: nonBackPreds[i] = make(map[int]bool)

. . 289: }

...

It looks like the current bottleneck is the same as the last one: using maps where

simpler data structures suffice.

FindLoops is allocating about 29.5 MB of maps.

As an aside, if we run go tool pprof with the --inuse_objects flag, it will

report allocation counts instead of sizes:

$ go tool pprof --inuse_objects havlak3 havlak3.mprof

Adjusting heap profiles for 1-in-524288 sampling rate

Welcome to pprof! For help, type 'help'.

(pprof) list FindLoops

Total: 1763108 objects

ROUTINE ====================== main.FindLoops in /home/rsc/g/benchgraffiti/havlak/havlak3.go

720903 720903 Total objects (flat / cumulative)

...

. . 277: for i := 0; i < size; i++ {

311296 311296 278: nodes[i] = new(UnionFindNode)

. . 279: }

. . 280:

. . 281: // Step a:

. . 282: // - initialize all nodes as unvisited.

. . 283: // - depth-first traversal and numbering.

. . 284: // - unreached BB's are marked as dead.

. . 285: //

. . 286: for i, bb := range cfgraph.Blocks {

. . 287: number[bb.Name] = unvisited

409600 409600 288: nonBackPreds[i] = make(map[int]bool)

. . 289: }

...

(pprof)

Since the ~200,000 maps account for 29.5 MB, it looks like the initial map allocation takes about 150 bytes. That’s reasonable when a map is being used to hold key-value pairs, but not when a map is being used as a stand-in for a simple set, as it is here.

Instead of using a map, we can use a simple slice to list the elements.

In all but one of the cases where maps are being used, it is impossible for the algorithm

to insert a duplicate element.

In the one remaining case, we can write a simple variant of the append built-in function:

func appendUnique(a []int, x int) []int {

for _, y := range a {

if x == y {

return a

}

}

return append(a, x)

}

In addition to writing that function, changing the Go program to use slices instead of maps requires changing just a few lines of code.

$ make havlak4

go build havlak4.go

$ ./xtime ./havlak4

# of loops: 76000 (including 1 artificial root node)

11.84u 0.08s 11.94r 810416kB ./havlak4

$

(See the diff from havlak3)

We’re now at 2.11x faster than when we started. Let’s look at a CPU profile again.

$ make havlak4.prof

./havlak4 -cpuprofile=havlak4.prof

# of loops: 76000 (including 1 artificial root node)

$ go tool pprof havlak4 havlak4.prof

Welcome to pprof! For help, type 'help'.

(pprof) top10

Total: 1173 samples

205 17.5% 17.5% 1083 92.3% main.FindLoops

138 11.8% 29.2% 215 18.3% scanblock

88 7.5% 36.7% 96 8.2% sweepspan

76 6.5% 43.2% 597 50.9% runtime.mallocgc

75 6.4% 49.6% 78 6.6% runtime.settype_flush

74 6.3% 55.9% 75 6.4% flushptrbuf

64 5.5% 61.4% 64 5.5% runtime.memmove

63 5.4% 66.8% 524 44.7% runtime.growslice

51 4.3% 71.1% 51 4.3% main.DFS

50 4.3% 75.4% 146 12.4% runtime.MCache_Alloc

(pprof)

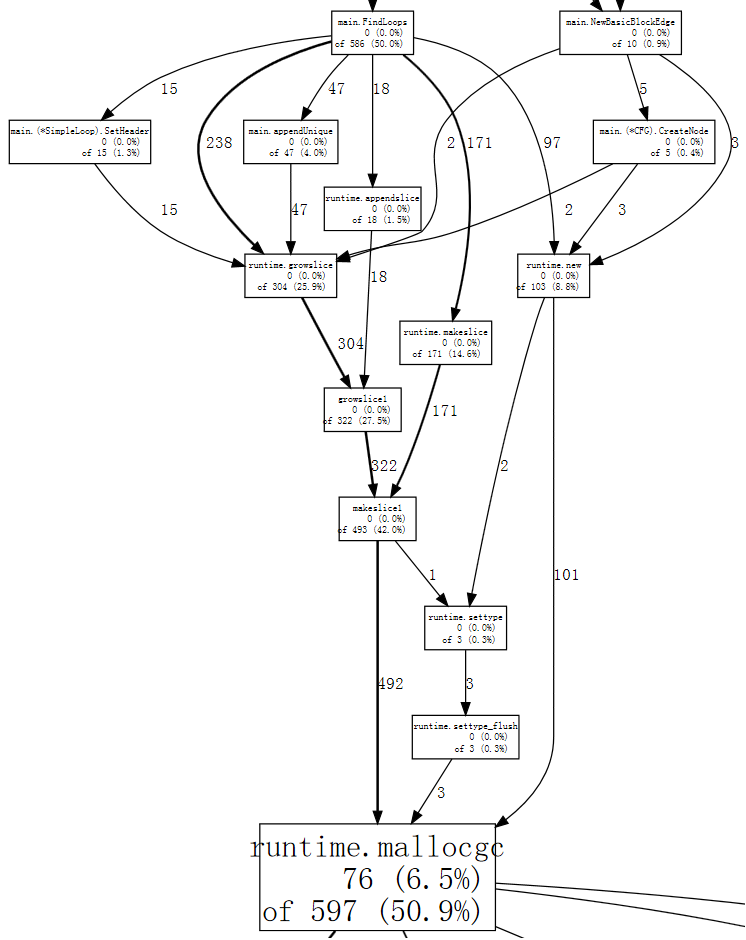

Now memory allocation and the consequent garbage collection (runtime.mallocgc)

accounts for 50.9% of our run time.

Another way to look at why the system is garbage collecting is to look at the

allocations that are causing the collections, the ones that spend most of the time

in mallocgc:

(pprof) web mallocgc

It’s hard to tell what’s going on in that graph, because there are many nodes with

small sample numbers obscuring the big ones.

We can tell go tool pprof to ignore nodes that don’t account for at least 10% of

the samples:

$ go tool pprof --nodefraction=0.1 havlak4 havlak4.prof

Welcome to pprof! For help, type 'help'.

(pprof) web mallocgc

We can follow the thick arrows easily now, to see that FindLoops is triggering

most of the garbage collection.

If we list FindLoops we can see that much of it is right at the beginning:

(pprof) list FindLoops

...

. . 270: func FindLoops(cfgraph *CFG, lsgraph *LSG) {

. . 271: if cfgraph.Start == nil {

. . 272: return

. . 273: }

. . 274:

. . 275: size := cfgraph.NumNodes()

. . 276:

. 145 277: nonBackPreds := make([][]int, size)

. 9 278: backPreds := make([][]int, size)

. . 279:

. 1 280: number := make([]int, size)

. 17 281: header := make([]int, size, size)

. . 282: types := make([]int, size, size)

. . 283: last := make([]int, size, size)

. . 284: nodes := make([]*UnionFindNode, size, size)

. . 285:

. . 286: for i := 0; i < size; i++ {

2 79 287: nodes[i] = new(UnionFindNode)

. . 288: }

...

(pprof)

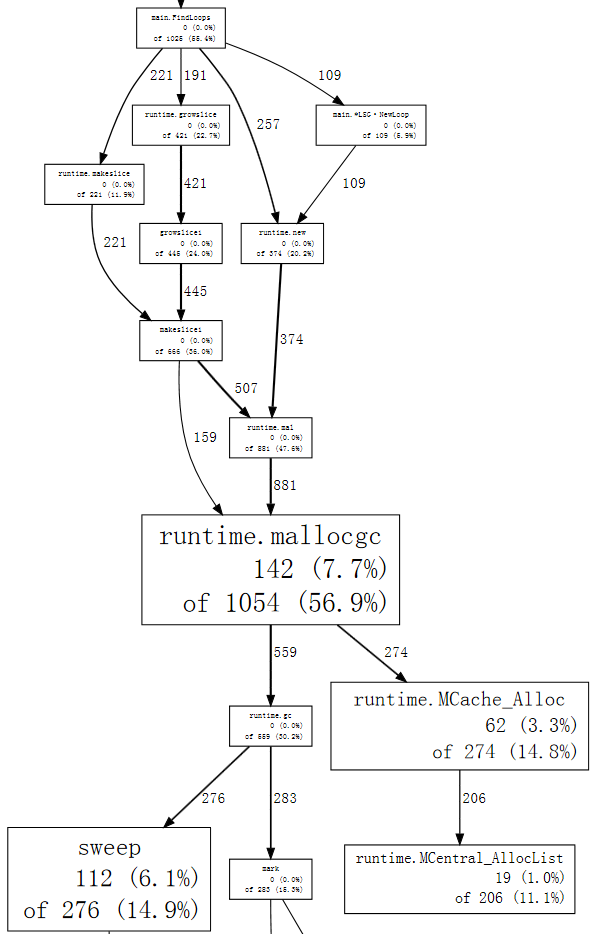

Every time FindLoops is called, it allocates some sizable bookkeeping structures.

Since the benchmark calls FindLoops 50 times, these add up to a significant amount

of garbage, so a significant amount of work for the garbage collector.

Having a garbage-collected language doesn’t mean you can ignore memory allocation

issues.

In this case, a simple solution is to introduce a cache so that each call to FindLoops

reuses the previous call’s storage when possible.

(In fact, in Hundt’s paper, he explains that the Java program needed just this change to

get anything like reasonable performance, but he did not make the same change in the

other garbage-collected implementations.)

We’ll add a global cache structure:

var cache struct {

size int

nonBackPreds [][]int

backPreds [][]int

number []int

header []int

types []int

last []int

nodes []*UnionFindNode

}

and then have FindLoops consult it as a replacement for allocation:

if cache.size < size {

cache.size = size

cache.nonBackPreds = make([][]int, size)

cache.backPreds = make([][]int, size)

cache.number = make([]int, size)

cache.header = make([]int, size)

cache.types = make([]int, size)

cache.last = make([]int, size)

cache.nodes = make([]*UnionFindNode, size)

for i := range cache.nodes {

cache.nodes[i] = new(UnionFindNode)

}

}

nonBackPreds := cache.nonBackPreds[:size]

for i := range nonBackPreds {

nonBackPreds[i] = nonBackPreds[i][:0]

}

backPreds := cache.backPreds[:size]

for i := range nonBackPreds {

backPreds[i] = backPreds[i][:0]

}

number := cache.number[:size]

header := cache.header[:size]

types := cache.types[:size]

last := cache.last[:size]

nodes := cache.nodes[:size]

Such a global variable is bad engineering practice, of course: it means that

concurrent calls to FindLoops are now unsafe.

For now, we are making the minimal possible changes in order to understand what

is important for the performance of our program; this change is simple and mirrors

the code in the Java implementation.

The final version of the Go program will use a separate LoopFinder instance to

track this memory, restoring the possibility of concurrent use.

$ make havlak5

go build havlak5.go

$ ./xtime ./havlak5

# of loops: 76000 (including 1 artificial root node)

8.03u 0.06s 8.11r 770352kB ./havlak5

$

(See the diff from havlak4)

There’s more we can do to clean up the program and make it faster, but none of

it requires profiling techniques that we haven’t already shown.

The work list used in the inner loop can be reused across iterations and across

calls to FindLoops, and it can be combined with the separate “node pool” generated

during that pass.

Similarly, the loop graph storage can be reused on each iteration instead of reallocated.

In addition to these performance changes, the

final version

is written using idiomatic Go style, using data structures and methods.

The stylistic changes have only a minor effect on the run time: the algorithm and

constraints are unchanged.

The final version runs in 2.29 seconds and uses 351 MB of memory:

$ make havlak6

go build havlak6.go

$ ./xtime ./havlak6

# of loops: 76000 (including 1 artificial root node)

2.26u 0.02s 2.29r 360224kB ./havlak6

$

That’s 11 times faster than the program we started with. Even if we disable reuse of the generated loop graph, so that the only cached memory is the loop finding bookeeping, the program still runs 6.7x faster than the original and uses 1.5x less memory.

$ ./xtime ./havlak6 -reuseloopgraph=false

# of loops: 76000 (including 1 artificial root node)

3.69u 0.06s 3.76r 797120kB ./havlak6 -reuseloopgraph=false

$

Of course, it’s no longer fair to compare this Go program to the original C++

program, which used inefficient data structures like sets where vectors would

be more appropriate.

As a sanity check, we translated the final Go program into

equivalent C++ code.

Its execution time is similar to the Go program’s:

$ make havlak6cc

g++ -O3 -o havlak6cc havlak6.cc

$ ./xtime ./havlak6cc

# of loops: 76000 (including 1 artificial root node)

1.99u 0.19s 2.19r 387936kB ./havlak6cc

The Go program runs almost as fast as the C++ program. As the C++ program is using automatic deletes and allocation instead of an explicit cache, the C++ program a bit shorter and easier to write, but not dramatically so:

$ wc havlak6.cc; wc havlak6.go

401 1220 9040 havlak6.cc

461 1441 9467 havlak6.go

$

(See havlak6.cc and havlak6.go)

Benchmarks are only as good as the programs they measure.

We used go tool pprof to study an inefficient Go program and then to improve its

performance by an order of magnitude and to reduce its memory usage by a factor of 3.7.

A subsequent comparison with an equivalently optimized C++ program shows that Go can be

competitive with C++ when programmers are careful about how much garbage is generated

by inner loops.

The program sources, Linux x86-64 binaries, and profiles used to write this post are available in the benchgraffiti project on GitHub.

As mentioned above, go test includes

these profiling flags already: define a

benchmark function and you’re all set.

There is also a standard HTTP interface to profiling data. In an HTTP server, adding

import _ "net/http/pprof"

will install handlers for a few URLs under /debug/pprof/.

Then you can run go tool pprof with a single argument—the URL to your server’s

profiling data and it will download and examine a live profile.

go tool pprof http://localhost:6060/debug/pprof/profile # 30-second CPU profile

go tool pprof http://localhost:6060/debug/pprof/heap # heap profile

go tool pprof http://localhost:6060/debug/pprof/block # goroutine blocking profile

The goroutine blocking profile will be explained in a future post. Stay tuned.

Next article: First Class Functions in Go

Previous article: Spotlight on external Go libraries

Blog Index