Go for Javaneros (Javaïstes?)

#go4java

Francesc Campoy

Gopher and Developer Advocate

Francesc Campoy

Gopher and Developer Advocate

Go is an open-source programming language

Google:

Others:

Minimal design

Orthogonal features

“The ratio of time spent reading (code) versus writing is well over 10 to 1 ... (therefore) making it easy to read makes it easier to write.”

― Robert C. Martin

Type safety, no buffer overflows, no pointer arithmetic.

“In a concurrent world, imperative is the wrong default!” - Tim Sweeney

Communicating Sequential Processes - Hoare (1978)

Go and Java are

Go is Object Oriented, but doesn't have the keywords:

class,extends, orimplements.int, uint, int8, uint8, ... bool, string float32, float64 complex64, complex128

struct {

Name string

Age int

}[]int, [3]string, []struct{ Name string }map[string]int

*int, *Person

func(int, int) int

chan bool

interface {

Start()

Stop()

}type [name] [specification]

Person is a struct type.

type Person struct {

name string

age int

}

Celsius is a float64 type.

type Celsius float64

func [name] ([params]) [return value] func [name] ([params]) ([return values])

A sum function:

func sum(a int, b int) int {

return a + b

}A function with multiple returned values:

func div(a, b int) (int, int)

return a / b, a % b

}Made clearer by naming the return values:

func div(den, div int) (q, rem int)

return a / b, a % b

}func ([receiver]) [name] ([params]) ([return values])

A method on a struct:

func (p Person) Major() bool {

return p.age >= 18

}

But also a method on a float64:

func (c Celsius) Freezing() bool {

return c <= 0

}Constraint: Methods can be defined only on types declared in the same package.

// This won't compile

func (s string) Length() int { return len(s) }

Use & to obtain the address of a variable.

a := "hello" p := &a

Use * to dereference the pointer.

fmt.Print(*p + ", world")

No pointer arithmetic, no pointers to unsafe memory.

a := "hello" p := &a p += 4 // no, you can't

Control what you pass to functions.

func double(x int) {

x *= 2

}func double(x *int) {

*x *= 2

}Control your memory layout.

Receivers behave like any other argument.

Pointers allow modifying the pointed receiver:

func (p *Person) IncAge() {

p.age++

}The method receiver is a copy of a pointer (pointing to the same address).

Method calls on nil receivers are perfectly valid (and useful!).

func (p *Person) Name() string {

if p == nil {

return "anonymous"

}

return p.name

}An interface is a set of methods.

In Java:

interface Switch {

void open();

void close();

}In Go:

type OpenCloser interface {

Open()

Close()

}Java interfaces are satisfied explicitly.

Go interfaces are satisfied implicitly.

If a type defines all the methods of an interface, the type satisfies that interface.

Benefits:

Think static duck typing, verified at compile time.

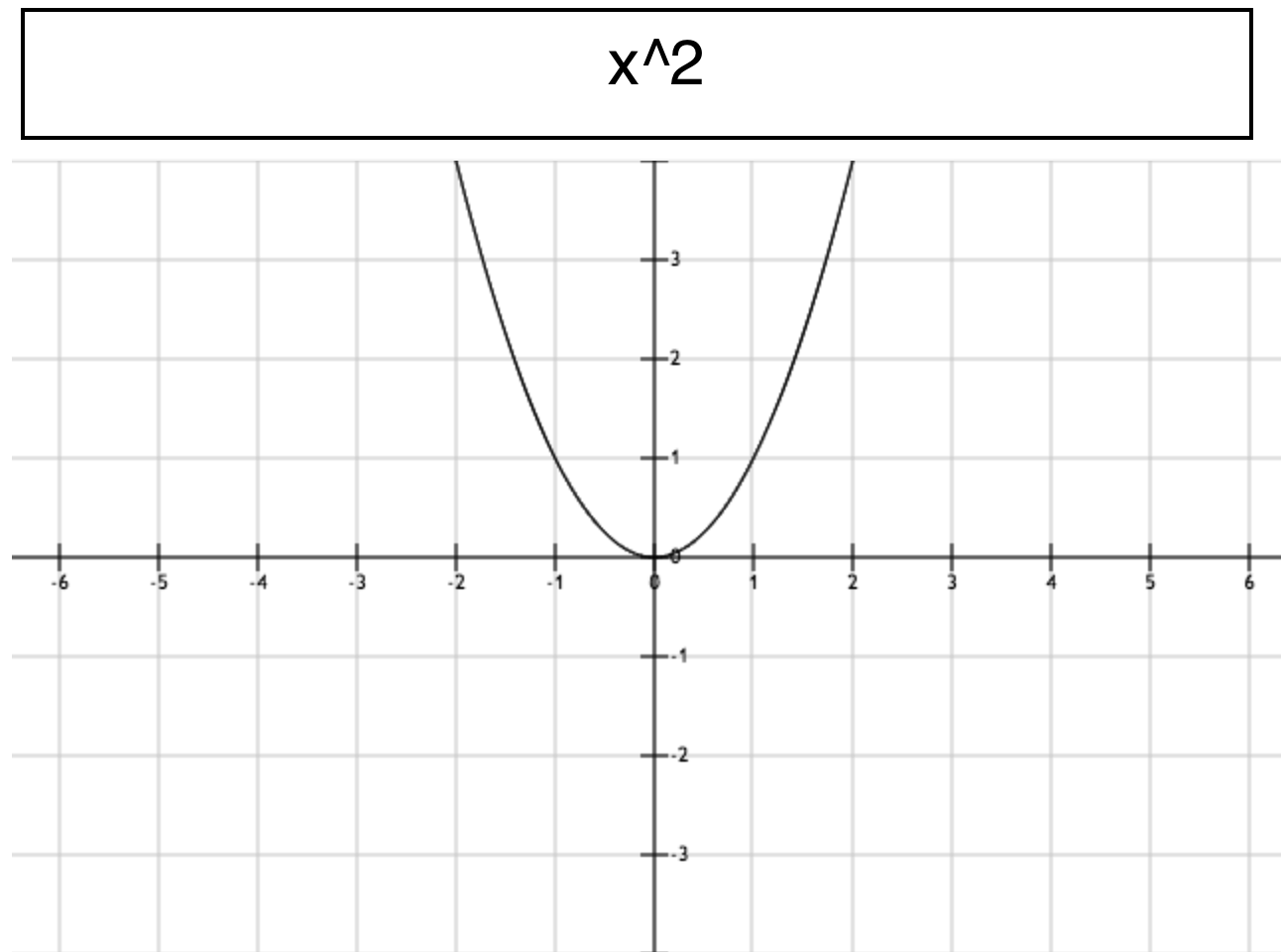

Package parse provides a parser of strings into functions.

func Parse(text string) (*Func, error) { ... }

Func is a struct type, with an Eval method.

type Func struct { ... }

func (p *Func) Eval(x float64) float64 { ... }Package draw generates images given a function.

func Draw(f *parser.Func) image.Image {

for x := start; x < end; x += inc {

y := f.Eval(x)

...

}

}

draw depends on parser

Let's use an interface instead

type Evaluable interface {

Eval(float64) float64

}

func Draw(f Evaluable) image.Image { ... }Lots of articles have been written about the topic.

In general, composition is preferred to inheritance.

Lets see why.

33class Runner { private String name; public Runner(String name) { this.name = name; } public String getName() { return this.name; } public void run(Task task) { task.run(); } public void runAll(Task[] tasks) { for (Task task : tasks) { run(task); } } }

class RunCounter extends Runner { private int count; public RunCounter(String message) { super(message); this.count = 0; } @Override public void run(Task task) { count++; super.run(task); } @Override public void runAll(Task[] tasks) { count += tasks.length; super.runAll(tasks); } public int getCount() { return count; } }

What will this code print?

RunCounter runner = new RunCounter("my runner"); Task[] tasks = { new Task("one"), new Task("two"), new Task("three")}; runner.runAll(tasks); System.out.printf("%s ran %d tasks\n", runner.getName(), runner.getCount());

Of course, this prints:

running one running two running three my runner ran 6 tasks

Wait! How many?

36Inheritance causes:

class RunCounter { private Runner runner; private int count; public RunCounter(String message) { this.runner = new Runner(message); this.count = 0; } public void run(Task task) { count++; runner.run(task); } public void runAll(Task[] tasks) { count += tasks.length; runner.runAll(tasks); } // continued on next slide ...

public int getCount() { return count; } public String getName() { return runner.getName(); } }

Pros

Runner is completely independent of RunCounter.Runner can be delayed until (and if) needed.Cons

Runner methods on RunCounter:public String getName() { return runner.getName(); }Let's use composition directly:

type Runner struct{ name string } func (r *Runner) Name() string { return r.name } func (r *Runner) Run(t Task) { t.Run() } func (r *Runner) RunAll(ts []Task) { for _, t := range ts { r.Run(t) } }

All very similar to the Java version.

42

RunCounter has a Runner field.

type RunCounter struct { runner Runner count int } func NewRunCounter(name string) *RunCounter { return &RunCounter{runner: Runner{name}} } func (r *RunCounter) Run(t Task) { r.count++ r.runner.Run(t) } func (r *RunCounter) RunAll(ts []Task) { r.count += len(ts) r.runner.RunAll(ts) } func (r *RunCounter) Count() int { return r.count } func (r *RunCounter) Name() string { return r.runner.Name() }

Same pros and cons as the composition version in Java.

We also have the boilerplate to proxy methods from Runner.

func (r *RunCounter) Name() string { return r.runner.Name() }

But we can remove it!

44Expressed in Go as unnamed fields in a struct.

It is still composition.

The fields and methods of the embedded type are defined on the embedding type.

Similar to inheritance, but the embedded type doesn't know it's embedded.

45

Given a type Person:

type Person struct{ Name string } func (p Person) Introduce() { fmt.Println("Hi, I'm", p.Name) }

We can define a type Employee embedding Person:

type Employee struct { Person EmployeeID int }

All fields and methods from Person are available on Employee:

var e Employee e.Name = "Peter" e.EmployeeID = 1234 e.Introduce()

type RunCounter2 struct { Runner count int } func NewRunCounter2(name string) *RunCounter2 { return &RunCounter2{Runner{name}, 0} } func (r *RunCounter2) Run(t Task) { r.count++ r.Runner.Run(t) } func (r *RunCounter2) RunAll(ts []Task) { r.count += len(ts) r.Runner.RunAll(ts) } func (r *RunCounter2) Count() int { return r.count }

No, it is better!

It is composition.

It is more general.

Struct embedding is selective.

// WriteCounter tracks the total number of bytes written. type WriteCounter struct { io.ReadWriter count int } func (w *WriteCounter) Write(b []byte) (int, error) { w.count += len(b) return w.ReadWriter.Write(b) }

WriteCounter can be used with any io.ReadWriter.

// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import (

"bytes"

"fmt"

"io"

"os"

)

var (

_ = bytes.Buffer{}

_ = os.Stdout

)

// WriteCounter tracks the total number of bytes written.

type WriteCounter struct {

io.ReadWriter

count int

}

func (w *WriteCounter) Write(b []byte) (int, error) {

w.count += len(b)

return w.ReadWriter.Write(b)

}

// MAIN OMIT

func main() { buf := &bytes.Buffer{} w := &WriteCounter{ReadWriter: buf} fmt.Fprintf(w, "Hello, gophers!\n") fmt.Printf("Printed %v bytes", w.count) }

What if we wanted to fake a part of a net.Conn?

type Conn interface {

Read(b []byte) (n int, err error)

Write(b []byte) (n int, err error)

Close() error

LocalAddr() Addr

RemoteAddr() Addr

SetDeadline(t time.Time) error

SetReadDeadline(t time.Time) error

SetWriteDeadline(t time.Time) error

}

I want to test handleCon:

func handleConn(conn net.Conn) {

fakeConn and define all the methods of Conn on it.WARNING : Cool stuff

If a type T has an embedded field of a type E, all the methods of E will be defined on T.

Therefore, if E is an interface T satisfies E.

51

We can test handleCon with the loopBack type.

type loopBack struct { net.Conn buf bytes.Buffer }

Any calls to the methods of net.Conn will fail, since the field is nil.

We redefine the operations we support:

func (c *loopBack) Read(b []byte) (int, error) { return c.buf.Read(b) } func (c *loopBack) Write(b []byte) (int, error) { return c.buf.Write(b) }

It is part of the language, not a library.

Based on two concepts:

So cheap you can use them whenever you want.

func sleepAndTalk(t time.Duration, msg string) { time.Sleep(t) fmt.Printf("%v ", msg) }

We want a message per second.

// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func sleepAndTalk(t time.Duration, msg string) {

time.Sleep(t)

fmt.Printf("%v ", msg)

}

func main() { sleepAndTalk(0*time.Second, "Hello") sleepAndTalk(1*time.Second, "Gophers!") sleepAndTalk(2*time.Second, "What's") sleepAndTalk(3*time.Second, "up?") }

What if we started all the sleepAndTalk concurrently?

Just add go!

// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func sleepAndTalk(t time.Duration, msg string) {

time.Sleep(t)

fmt.Printf("%v ", msg)

}

func main() { go sleepAndTalk(0*time.Second, "Hello") go sleepAndTalk(1*time.Second, "Gophers!") go sleepAndTalk(2*time.Second, "What's") go sleepAndTalk(3*time.Second, "up?") }

That was fast ...

When the main goroutine ends, the program ends.

// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func sleepAndTalk(t time.Duration, msg string) {

time.Sleep(t)

fmt.Printf("%v ", msg)

}

func main() { go sleepAndTalk(0*time.Second, "Hello") go sleepAndTalk(1*time.Second, "Gophers!") go sleepAndTalk(2*time.Second, "What's") go sleepAndTalk(3*time.Second, "up?") time.Sleep(4 * time.Second) }

But synchronizing with Sleep is a bad idea.

sleepAndTalk sends the string into the channel instead of printing it.

func sleepAndTalk(secs time.Duration, msg string, c chan string) { time.Sleep(secs * time.Second) c <- msg }

We create the channel and pass it to sleepAndTalk, then wait for the values to be sent.

// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func sleepAndTalk(secs time.Duration, msg string, c chan string) {

time.Sleep(secs * time.Second)

c <- msg

}

func main() { c := make(chan string) go sleepAndTalk(0, "Hello", c) go sleepAndTalk(1, "Gophers!", c) go sleepAndTalk(2, "What's", c) go sleepAndTalk(3, "up?", c) for i := 0; i < 4; i++ { fmt.Printf("%v ", <-c) } }

We receive the next id from a channel.

var nextID = make(chan int) func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, q *http.Request) { fmt.Fprintf(w, "<h1>You got %v<h1>", <-nextID) }

We need a goroutine sending ids into the channel.

// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import (

"fmt"

"net/http"

)

var nextID = make(chan int)

func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, q *http.Request) {

fmt.Fprintf(w, "<h1>You got %v<h1>", <-nextID)

}

func main() { http.HandleFunc("/next", handler) go func() { for i := 0; ; i++ { nextID <- i } }() http.ListenAndServe("localhost:8080", nil) }

select allows us to chose among multiple channel operations.

// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import (

"fmt"

"net/http"

)

var battle = make(chan string) func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, q *http.Request) { select { case battle <- q.FormValue("usr"): fmt.Fprintf(w, "You won!") case won := <-battle: fmt.Fprintf(w, "You lost, %v is better than you", won) } }

func main() {

http.HandleFunc("/fight", handler)

http.ListenAndServe("localhost:8080", nil)

}

Go - localhost:8080/fight?usr=go

Java - localhost:8080/fight?usr=java

Ok, I'm just bragging here

61// +build ignore,OMIT

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func f(left, right chan int) { left <- 1 + <-right } func main() { start := time.Now() const n = 1000 leftmost := make(chan int) right := leftmost left := leftmost for i := 0; i < n; i++ { right = make(chan int) go f(left, right) left = right } go func(c chan int) { c <- 0 }(right) fmt.Println(<-leftmost, time.Since(start)) }

And there's lots to learn!

Go is simple, consistent, readable, and fun.

All types are equal

Implicit interfaces

Use composition instead of inheritance

Concurrency is awesome, and you should check it out.

64Learn Go on your browser with tour.golang.org

Find more about Go on golang.org

Join the community at golang-nuts

Link to the slides go.dev/talks/2014/go4java.slide

65