The Go Blog

An Introduction To Generics

Introduction

This blog post is based on our talk at GopherCon 2021:

The Go 1.18 release adds support for generics. Generics are the biggest change we’ve made to Go since the first open source release. In this article we’ll introduce the new language features. We won’t try to cover all the details, but we will hit all the important points. For a more detailed and much longer description, including many examples, see the proposal document. For a more precise description of the language changes, see the updated language spec. (Note that the actual 1.18 implementation imposes some restrictions on what the proposal document permits; the spec should be accurate. Future releases may lift some of the restrictions.)

Generics are a way of writing code that is independent of the specific types being used. Functions and types may now be written to use any of a set of types.

Generics adds three new big things to the language:

- Type parameters for function and types.

- Defining interface types as sets of types, including types that don’t have methods.

- Type inference, which permits omitting type arguments in many cases when calling a function.

Type Parameters

Functions and types are now permitted to have type parameters. A type parameter list looks like an ordinary parameter list, except that it uses square brackets instead of parentheses.

To show how this works, let’s start with the basic non-generic Min

function for floating point values:

func Min(x, y float64) float64 {

if x < y {

return x

}

return y

}

We can make this function generic–make it work for different

types–by adding a type parameter list.

In this example we add a type parameter list with a single type

parameter T, and replace the uses of float64 with T.

import "golang.org/x/exp/constraints"

func GMin[T constraints.Ordered](x, y T) T {

if x < y {

return x

}

return y

}

It is now possible to call this function with a type argument by writing a call like

x := GMin[int](2, 3)

Providing the type argument to GMin, in this case int, is called

instantiation.

Instantiation happens in two steps.

First, the compiler substitutes all type arguments for their

respective type parameters throughout the generic function or type.

Second, the compiler verifies that each type argument satisfies the

respective constraint.

We’ll get to what that means shortly, but if that second step fails,

instantiation fails and the program is invalid.

After successful instantiation we have a non-generic function that can be called just like any other function. For example, in code like

fmin := GMin[float64]

m := fmin(2.71, 3.14)

the instantiation GMin[float64] produces what is effectively our

original floating-point Min function, and we can use that in a

function call.

Type parameters can be used with types also.

type Tree[T interface{}] struct {

left, right *Tree[T]

value T

}

func (t *Tree[T]) Lookup(x T) *Tree[T] { ... }

var stringTree Tree[string]

Here the generic type Tree stores values of the type parameter T.

Generic types can have methods, like Lookup in this example.

In order to use a generic type, it must be instantiated;

Tree[string] is an example of instantiating Tree with the type

argument string.

Type sets

Let’s look a bit deeper at the type arguments that can be used to instantiate a type parameter.

An ordinary function has a type for each value parameter; that type

defines a set of values.

For instance, if we have a float64 type as in the non-generic

function Min above, the permissible set of argument values is the

set of floating-point values that can be represented by the float64

type.

Similarly, type parameter lists have a type for each type parameter. Because a type parameter is itself a type, the types of type parameters define sets of types. This meta-type is called a type constraint.

In the generic GMin, the type constraint is imported from the

constraints package.

The Ordered constraint describes the set of all types with values

that can be ordered, or, in other words, compared with the <

operator (or <= , > , etc.).

The constraint ensures that only types with orderable values can be

passed to GMin.

It also means that in the GMin function body values of that type

parameter can be used in a comparison with the < operator.

In Go, type constraints must be interfaces.

That is, an interface type can be used as a value type, and it can

also be used as a meta-type.

Interfaces define methods, so obviously we can express type

constraints that require certain methods to be present.

But constraints.Ordered is an interface type too, and the <

operator is not a method.

To make this work, we look at interfaces in a new way.

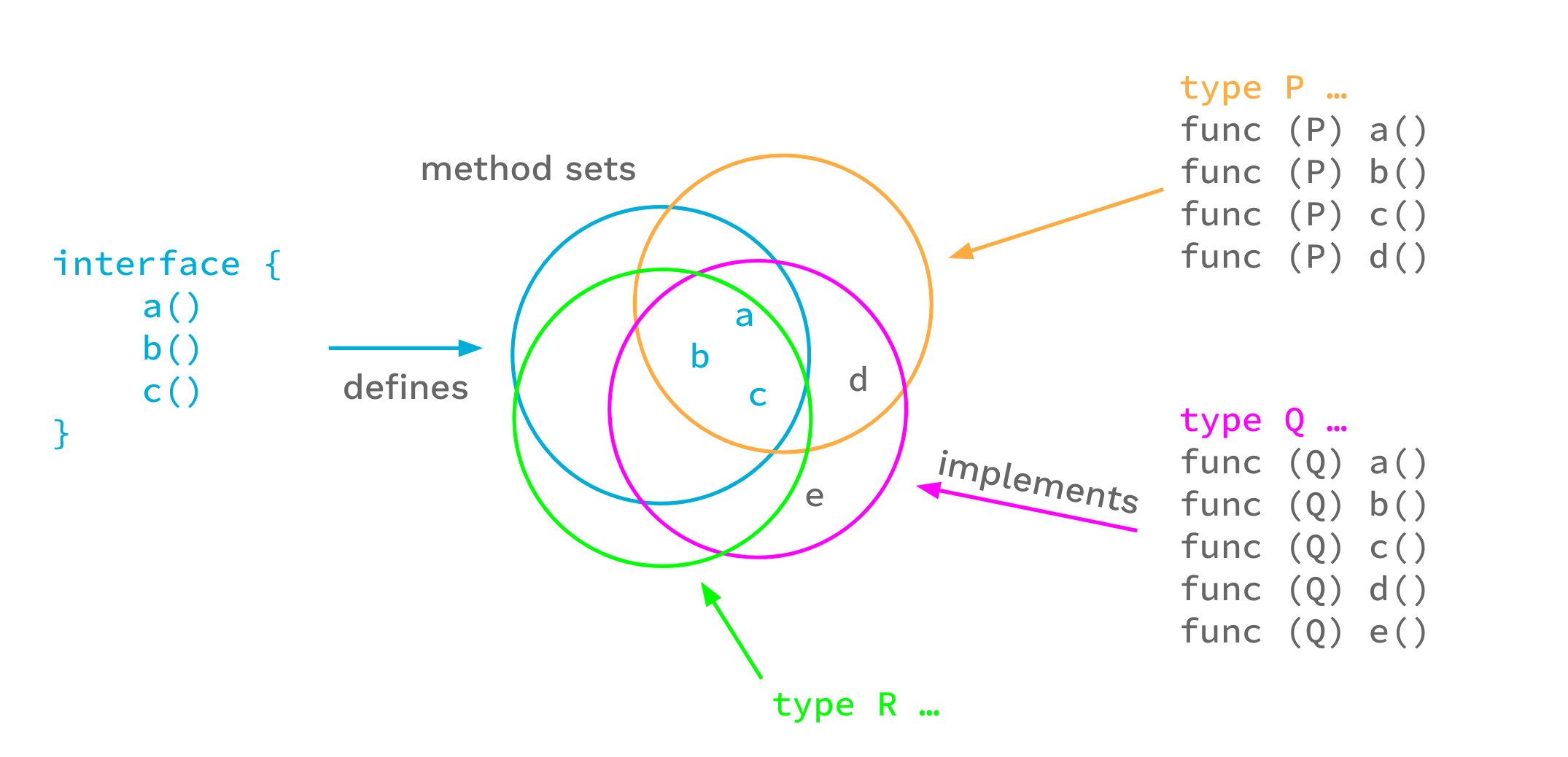

Until recently, the Go spec said that an interface defines a method set, which is roughly the set of methods enumerated in the interface. Any type that implements all those methods implements that interface.

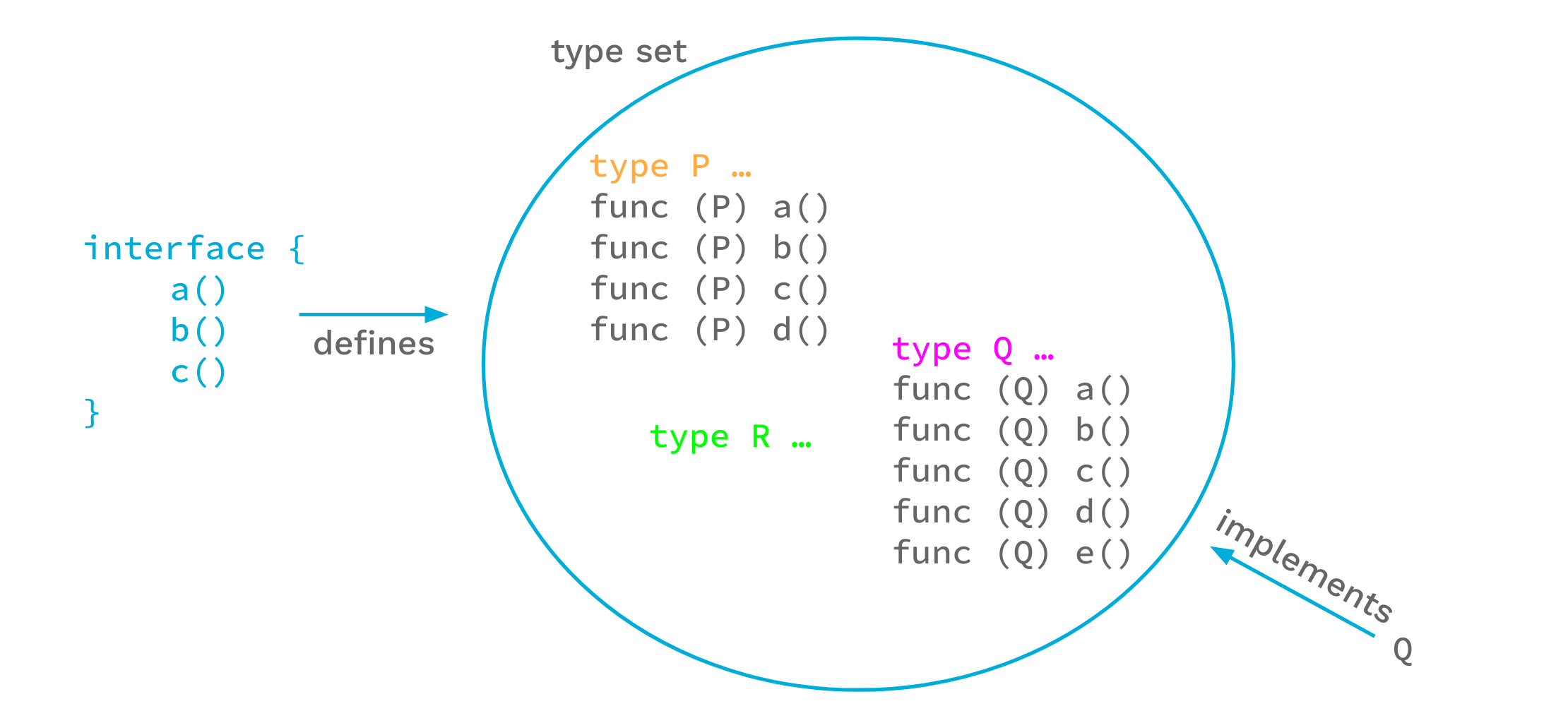

But another way of looking at this is to say that the interface defines a set of types, namely the types that implement those methods. From this perspective, any type that is an element of the interface’s type set implements the interface.

The two views lead to the same outcome: For each set of methods we can imagine the corresponding set of types that implement those methods, and that is the set of types defined by the interface.

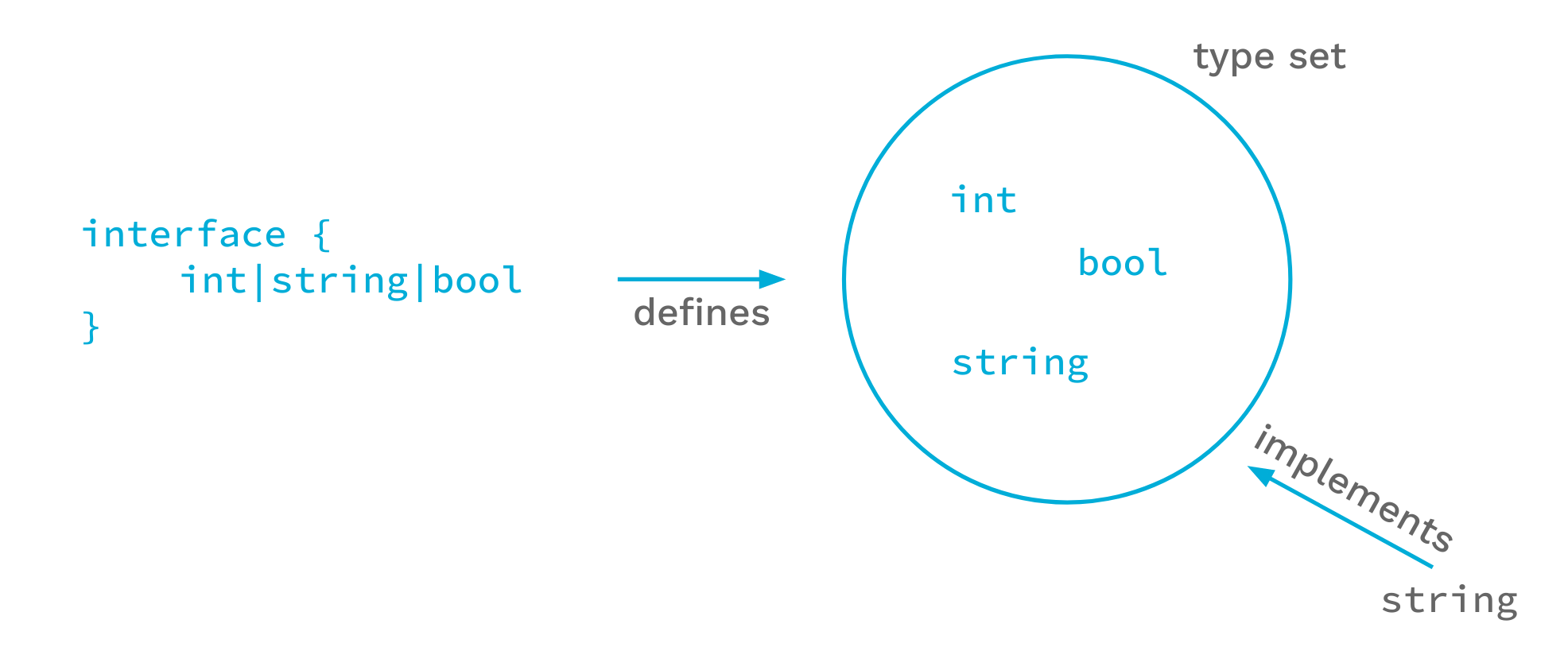

For our purposes, though, the type set view has an advantage over the method set view: we can explicitly add types to the set, and thus control the type set in new ways.

We have extended the syntax for interface types to make this work.

For instance, interface{ int|string|bool } defines the type set

containing the types int, string, and bool.

Another way of saying this is that this interface is satisfied by

only int, string, or bool.

Now let’s look at the actual definition of constraints.Ordered:

type Ordered interface {

Integer|Float|~string

}

This declaration says that the Ordered interface is the set of all

integer, floating-point, and string types.

The vertical bar expresses a union of types (or sets of types in this

case).

Integer and Float are interface types that are similarly defined

in the constraints package.

Note that there are no methods defined by the Ordered interface.

For type constraints we usually don’t care about a specific type, such

as string; we are interested in all string types.

That is what the ~ token is for.

The expression ~string means the set of all types whose underlying

type is string.

This includes the type string itself as well as all types declared

with definitions such as type MyString string.

Of course we still want to specify methods in interfaces, and we want to be backward compatible. In Go 1.18 an interface may contain methods and embedded interfaces just as before, but it may also embed non-interface types, unions, and sets of underlying types.

When used as a type constraint, the type set defined by an interface

specifies exactly the types that are permitted as type arguments for

the respective type parameter.

Within a generic function body, if the type of a operand is a type

parameter P with constraint C, operations are permitted if they

are permitted by all types in the type set of C (there are currently

some implementation restrictions here, but ordinary code is unlikely

to encounter them).

Interfaces used as constraints may be given names (such as Ordered),

or they may be literal interfaces inlined in a type parameter list.

For example:

[S interface{~[]E}, E interface{}]

Here S must be a slice type whose element type can be any type.

Because this is a common case, the enclosing interface{} may be

omitted for interfaces in constraint position, and we can simply

write:

[S ~[]E, E interface{}]

Because the empty interface is common in type parameter lists, and in

ordinary Go code for that matter, Go 1.18 introduces a new predeclared

identifier any as an alias for the empty interface type.

With that, we arrive at this idiomatic code:

[S ~[]E, E any]

Interfaces as type sets is a powerful new mechanism and is key to making type constraints work in Go. For now, interfaces that use the new syntactic forms may only be used as constraints. But it’s not hard to imagine how explicitly type-constrained interfaces might be useful in general.

Type inference

The last new major language feature is type inference. In some ways this is the most complicated change to the language, but it is important because it lets people use a natural style when writing code that calls generic functions.

Function argument type inference

With type parameters comes the need to pass type arguments, which can

make for verbose code.

Going back to our generic GMin function:

func GMin[T constraints.Ordered](x, y T) T { ... }

the type parameter T is used to specify the types of the ordinary

non-type arguments x, and y.

As we saw earlier, this can be called with an explicit type argument

var a, b, m float64

m = GMin[float64](a, b) // explicit type argument

In many cases the compiler can infer the type argument for T from

the ordinary arguments.

This makes the code shorter while remaining clear.

var a, b, m float64

m = GMin(a, b) // no type argument

This works by matching the types of the arguments a and b with the

types of the parameters x, and y.

This kind of inference, which infers the type arguments from the types of the arguments to the function, is called function argument type inference.

Function argument type inference only works for type parameters that

are used in the function parameters, not for type parameters used only

in function results or only in the function body.

For example, it does not apply to functions like MakeT[T any]() T,

that only uses T for a result.

Constraint type inference

The language supports another kind of type inference, constraint type inference. To describe this, let’s start with this example of scaling a slice of integers:

// Scale returns a copy of s with each element multiplied by c.

// This implementation has a problem, as we will see.

func Scale[E constraints.Integer](s []E, c E) []E {

r := make([]E, len(s))

for i, v := range s {

r[i] = v * c

}

return r

}

This is a generic function that works for a slice of any integer type.

Now suppose that we have a multi-dimensional Point type, where each

Point is simply a list of integers giving the coordinates of the

point.

Naturally this type will have some methods.

type Point []int32

func (p Point) String() string {

// Details not important.

}

Sometimes we want to scale a Point.

Since a Point is just a slice of integers, we can use the Scale

function we wrote earlier:

// ScaleAndPrint doubles a Point and prints it.

func ScaleAndPrint(p Point) {

r := Scale(p, 2)

fmt.Println(r.String()) // DOES NOT COMPILE

}

Unfortunately this does not compile, failing with an error like

r.String undefined (type []int32 has no field or method String).

The problem is that the Scale function returns a value of type []E

where E is the element type of the argument slice.

When we call Scale with a value of type Point, whose underlying

type is []int32, we get back a value of type []int32, not type

Point.

This follows from the way that the generic code is written, but it’s

not what we want.

In order to fix this, we have to change the Scale function to use a

type parameter for the slice type.

// Scale returns a copy of s with each element multiplied by c.

func Scale[S ~[]E, E constraints.Integer](s S, c E) S {

r := make(S, len(s))

for i, v := range s {

r[i] = v * c

}

return r

}

We’ve introduced a new type parameter S that is the type of the

slice argument.

We’ve constrained it such that the underlying type is S rather than

[]E, and the result type is now S.

Since E is constrained to be an integer, the effect is the same as

before: the first argument has to be a slice of some integer type.

The only change to the body of the function is that now we pass S,

rather than []E, when we call make.

The new function acts the same as before if we call it with a plain

slice, but if we call it with the type Point we now get back a value

of type Point.

That is what we want.

With this version of Scale the earlier ScaleAndPrint function will

compile and run as we expect.

But it’s fair to ask: why is it OK to write the call to Scale

without passing explicit type arguments?

That is, why can we write Scale(p, 2), with no type arguments,

rather than having to write Scale[Point, int32](p, 2)?

Our new Scale function has two type parameters, S and E.

In a call to Scale not passing any type arguments, function argument

type inference, described above, lets the compiler infer that the type

argument for S is Point.

But the function also has a type parameter E which is the type of the

multiplication factor c.

The corresponding function argument is 2, and because 2 is an untyped

constant, function argument type inference cannot infer the correct type for

E (at best it might infer the default type for 2 which is int and which

would be incorrect).

Instead, the process by which the compiler infers that the type argument

for E is the element type of the slice is called constraint type

inference.

Constraint type inference deduces type arguments from type parameter constraints. It is used when one type parameter has a constraint defined in terms of another type parameter. When the type argument of one of those type parameters is known, the constraint is used to infer the type argument of the other.

The usual case where this applies is when one constraint uses the form

~type for some type, where that type is written using other type

parameters.

We see this in the Scale example.

S is ~[]E, which is ~ followed by a type []E written in terms

of another type parameter.

If we know the type argument for S we can infer the type argument

for E.

S is a slice type, and E is the element type of that slice.

This was just an introduction to constraint type inference. For full details see the proposal document document or the language spec.

Type inference in practice

The exact details of how type inference works are complicated, but using it is not: type inference either succeeds or fails. If it succeeds, type arguments can be omitted, and calling generic functions looks no different than calling ordinary functions. If type inference fails, the compiler will give an error message, and in those cases we can just provide the necessary type arguments.

In adding type inference to the language we’ve tried to strike a balance between inference power and complexity. We want to ensure that when the compiler infers types, those types are never surprising. We’ve tried to be careful to err on the side of failing to infer a type rather than on the side of inferring the wrong type. We probably have not gotten it entirely right, and we may continue to refine it in future releases. The effect will be that more programs can be written without explicit type arguments. Programs that don’t need type arguments today won’t need them tomorrow either.

Conclusion

Generics are a big new language feature in 1.18. These new language changes required a large amount of new code that has not had significant testing in production settings. That will only happen as more people write and use generic code. We believe that this feature is well implemented and high quality. However, unlike most aspects of Go, we can’t back up that belief with real world experience. Therefore, while we encourage the use of generics where it makes sense, please use appropriate caution when deploying generic code in production.

That caution aside, we’re excited to have generics available, and we hope that they will make Go programmers more productive.

Next article: How Go Mitigates Supply Chain Attacks

Previous article: Go 1.18 is released!

Blog Index